Since the late 1990’s, research has shown that Internet users are functionally blind to ads on a web page. In 2005, Burke, Hornof, Nilsen, and Gorman concluded,

Eye tracking data reveal people rarely look directly at banners. A post hoc memory test confirms low banner recall and, surprisingly, that animated banners are more difficult to remember than static look-alikes. Results have implications for cognitive modeling and Web design.

Top and Right are Deadly Locations for Banners

This banner blindness is particularly high when banner advertisements are located on the top or right of a web page. Unfortunately for us marketers, those are the locations most offered for ad space.

I’ve fought many a battle with trade publications about where and how to format ad space. I’ve won some and lost some. In those cases where I’ve convinced the magazine to place the ads in a different location – one that isn’t already associated with advertising – the ads have produced well. When stuck in the typical banner space, the ads do poorly.

It’s interesting to see publications like Industrial Laser Solutions now offering banner space that expands as you open the web page, converting the ad from a typical banner size to one that encompasses most of the page space above the fold.

What About Text-Based Pay Per Click Ads?

In a 2011 study on banner blindness and text advertising, Owens, Chaparro, and Palmer concluded that users are now exhibiting banner blindness to text ads, just like display and banner ads.

Hmmm based on the results of our clients’ PPC programs, I’m not convinced.

As previously covered in this blog, I am particularly interested in the research of Professor Soussan Djamasbi in the User Experience & Decision Making Research Lab at WPI. Her newest paper is, Do Ads Matter? An Exploration of Web Search Behavior, Visual Hierarchy, and Search Engine Results Pages. Djamasbi joined with fellow WPI researchers Assistant Professor Adrienne Hall Phillips and Ruijiao (Rachel) Yang (a former student of mine ). Using eye tracking experiments, they investigated how users view list formatted search engine ads. For those of us in the biz, these are also known as pay per click ads, like Google AdWords.

According to the authors,

Although location and type of search is a factor, users ignore ads unless perceived to be useful in completing their search task. We speculate users continue to exhibit this type of behavior because of the over-saturation of advertisements that tend to clutter the tops and sides of the web page. Would the presence of ads affect the attention to the returned search results? Do users spend more time looking at ads than at entries?

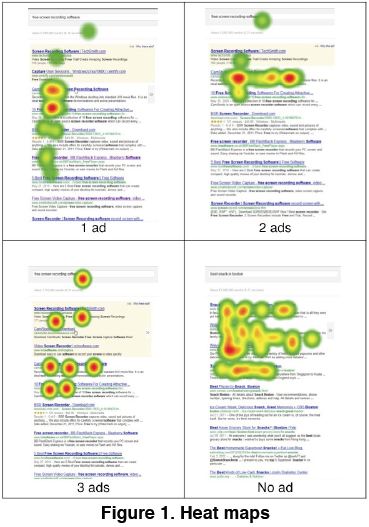

The WPI research asked study participants to search Google for specific keyword phrases. Eye tracking studies were then used to generate heat maps of viewing behavior. Results are shown in Figure 1.

NOTE: I am concerned that the phrases used generated only top of page ads (ads located above the search results). Google also displays ads down the right hand side of the SERP. Those were not included in this study.

Users Do Look at PPC Ads

The good news is this research showed that users do, in fact, look at text-based search engine ads. In this study, 77% of users look at the ads.

The analysis of the heat maps indicated that users looked at the advertisements and the top entries of the SERPs. The fixation patterns for these users appear to favor the top portion of the entries, including the advertisements if present. Users seem to neglect the lower portion of the page, including the numbers listed for the additional pages of results.

We expected all the users to ignore the advertisements generated by Google that were presented in the SERP. However, to our surprise, 77% of the users, who were presented ads, looked at the ads, contradicting the theory of banner blindness.

We discovered that users looked at more entries (entries 1 – 9) when there were no ads, but only six entries (entry 1 – 6) when ads were present. This is consistent with competition for attention theory, suggesting that when ads were present, fewer entries were viewed.

When at least one advertisement was presented, 9% of the subjects clicked on an entry (as opposed to scrolling) as their first action. Nearly 54% of the subjects clicked on an entry as their first action when there were no ads presented. The amount of time it takes for the user to get to their first action (clicking or scrolling) has a significant relationship with the number of ads on the page. As the number of ads decreases, so does the first action duration.

As an interesting side note, even when searching for free products or services, users still look at the PPC ads.

We expected that users who were looking for [the keyword phrase] -˜free screen recording’ would not look at advertisements, because these ads were for paid software products. However, our results showed that the users did look at the ads, although they knew they were required to look for free offerings. We believe that this is good news for marketers, since the ads get attention even at times when users are not necessarily looking for their products. However, our results showed that regardless of the number of ads present, users still only looked at one ad. This highlights the importance of ranking of ads on SERPs.

The problem is that the #1 PPC rank also results in extraneous clicks…clicks that you have to pay for. Some are people who click but didn’t mean to, some are students doing research but have no intention of buying, some are people who misread or misinterpreted your ad, etc.

Btw, what about for the search engines themselves? Obviously they love their advertisers and their ad budgets. Are there any negative implications of having ads run on their SERPs?

Our findings also suggest that the presence of ads had an impact on the number of entries that were viewed following the ads. When ads were present, fewer entries were viewed. This suggests that ads had a negative impact on how deep the search results were examined. This in turn, may result in a negative impact on user experience by discouraging users from fully utilizing the search results presented.

This leads me back to my prior post, Is Google Making Us Stupid, A Marketer’s Perspective. As we learn to search and browse through vast amounts of online info, our brains are changing (thanks to their neuroplasticity). We are becoming better at broad but shallow reading vs reading in depth.

Congrats if you make it to the end of this post. Lol