I had the pleasure of speaking at tech incubator TechSandBox this week on the state of the process control industry. Barb Finer, Executive Director of TSB and a long-time friend and colleague, grew up in the industry on a parallel path to mine. So I decided to focus on the evolution of two major disruptive innovation curves, both of which we experienced first hand as product managers at several of the leading innovators in programmable controllers and PC-based control systems. Let’s take a look at the evolution of the technologies and business models, and the wild consolidation that has occurred over the last 20 years.

——

The process control industry. People outside the market think what a boring industry with slow to change technology. Well, I’ve been knee deep in the controls market for 30 years and I can tell you, that is not the case.

In March 1959 following almost two and a half years of work Texaco and the Thompson Ramo Wooldridge (TRW) Co. installed the first direct digital control computer in a refinery. This would become known as the computer-integrated manufacturing (CIM) era.

In March 1959 following almost two and a half years of work Texaco and the Thompson Ramo Wooldridge (TRW) Co. installed the first direct digital control computer in a refinery. This would become known as the computer-integrated manufacturing (CIM) era.

BusinessWeek wrote, Shortly before 11 a.m. on March. 12, a veteran Texas Co. process operator named Marvin Voight flipped the switch … The action closed the loop in the first fully automatic, computer-controlled industrial process. Moments later, the most vital parts of the 1,800-bpd polymerization unit at Texaco’s Port Arthur (Texas) refinery were under the unblinking eye and almost instantaneous control of a Thompson Ramo Wooldridge Corp. RW-300, a desk-size digital computer designed for just such control jobs as this. Texaco hopes the computer will raise the plant’s efficiency by a healthy 6% to 10%.

Since then, it’s been a wild ride of innovations based on developments in I/O, computing platforms, services, and network connectivity.

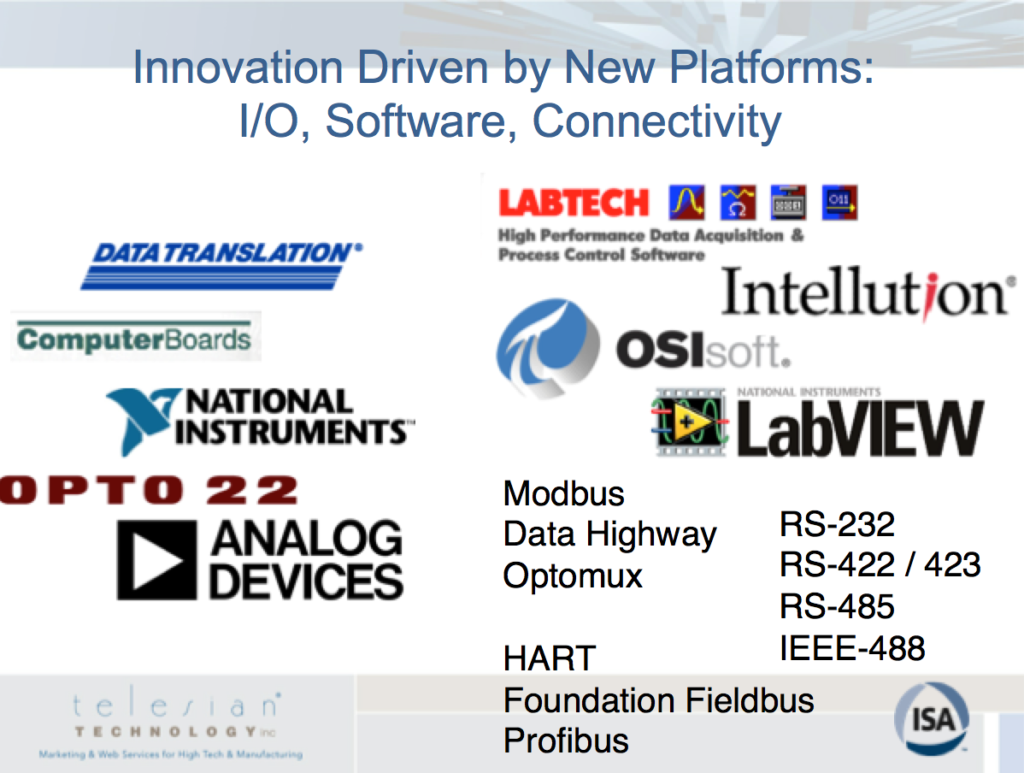

The introduction of the IBM PC and the rapid creation of a defacto bus standard, PCI bus, increased the pace of innovation.

In 1973, Fred Molinari, ex Analogic, started Data Translation to modularize analog I/O functions and put them on computer buses: Unibus, Q-bus, Multibus, and the IBM PC PCI bus. DTI and Tecmar were in a race to be the first to market. In 1976, National Instruments launched with a GPIB interface (first introduced as the HP-IB interface for instruments, then to become IEEE-488).

In 1981, Fred Putnam introduced LABTECH Notebook for the IBM PC, the first hardware-independent measurement and control software. At the same time, Steve Rubin founded Intellution and launched The Fix, which became the dominant PC-based HMI / control software. NI introduced LabVIEW for the Mac in 1986.

On the communications side, proprietary protocols like Modbus and AB’s Data Highway gave way to industry standards and open architecture systems.

The 1980’s and 1990’s were heady days. As PC’s moved from operator interfaces to control systems, tempers flared. Fred Putnam and Ed Kompass, long time editor of Control Engineering magazine, even ended up in a very public shouting match at a trade show about whether or not PC’s should be used for control.

Then the innovators started to be acquired

LABTECH was acquired by PC board vendor Measurement Computing, which also acquired Data Translation. Measurement Computing was acquired by National Instruments. National Instruments then combined LABTECH and Data Translation with other I/O businesses they had acquired: IOtech, Strawberry Tree, and Analogic’s board-level I/O business.

PC board vendor Computer Boards, founded by ex Keithley Instruments execs, changed it’s name to Metrabyte and was acquired by Keithley. Keithley was acquired by Tektronix. Tektronix was acquired by Danaher. Danaher is about to bring all it’s measurement and control businesses together into a new division, Fortive.

The behemoth control vendors were hungry for acquisitions, too. The original PLC was invented by Dick Morley and crew at Bedford Associates. Bedford became Modicon. Modicon was acquired by Gould Electronics, then by AEG. AEG was acquired by Schneider Electric. Schneider also acquired Foxboro (after they were acquired by Siebe) and Invensys.

Intellution was first acquired by Emerson Process. Originally a fans and motors company, Emerson also acquired Rosemount, Fisher Controls, and Micro Motion. Then Emerson sold Intellution to GE. I still think that was an odd move.

Confused yet? Lol.

Why such consolidation? Buyers are the primary force driving the industry. A small number of large manufacturers bought the bulk of the equipment. The fate of the process control vendors rose and fell with their customers. In the figure below, we see good news in aerospace products, electrical equipment, and basic chemicals. The low prices at the gas pump mean things aren’t so great for capital equipment purchases by oil and gas companies.

Moreover, there were million dollar production lines and batches that couldn’t afford to be offline. So Buyers were demanding more accountability, especially as they started shrinking their in-house engineering workforces.

Distribution channels were a challenge. Everyone had to go direct to the end customer or through a specially trained systems integrator because of the complexity of the products and processes.

The fastest road to innovation was happening in the smaller companies who were new entrants to the industry.

Two major business models dominate the market today:

- Broad range of services, customers including hardware, software, system integration services

- Focused product range. Over time, the focused product range companies are most likely to be acquired to expand large, integrated services

Let’s take a closer look at National Instruments, for example. Why did they not only survive but thrive?

First, they are fiercely independent. For decades, they have refused to sell.

Second, they had a unique mix of hardware, easy to use software that turned the industry on its head, expertise-building marketing created by a strong team of product managers, and what grew to be a large channel of partners.

Marketing is not something to be taken lightly. Ralph Grabowski did research at the request of the MIT Enterprise Forum on which tech companies succeeded an why. The bottom line clearly showed that the successful companies invested at least 2.5 as much in market research as they did in engineering. Yes, you read that right. AT LEAST 2.5x THE INVESTMENT IN MARKET RESEARCH. Then add other marketing activities and you end up with up to 10x the investment over engineering.

According to Harbor Research, automation companies are evolving from simple equipment monitoring and maintenance to integrated automation, monitoring, and asset mgmt, energy systems, and managed security

Some of the biggest opportunities for success are in plug-n-play KPI software that transcends all layers of the factory, from real-time plant floor data to the executive suite. Think something like the LabVIEW of business KPI’s.

The other big opportunity is the push for smaller, smarter, cheaper as part of the Internet of Things. Gartner says 6.4 billion connective “things” will be in use in 2016, up 30% from 2015. What I don’t understand is why the measurement and control sensor manufacturers aren’t all over this opportunity. They should be driving this big, exciting opportunity. For now, we have to settle for Cisco and GE arguing about whether to call it “Internet of Things,” “Internet of Everything,” or “Industrial Internet of Things.”

The other big opportunity is the push for smaller, smarter, cheaper as part of the Internet of Things. Gartner says 6.4 billion connective “things” will be in use in 2016, up 30% from 2015. What I don’t understand is why the measurement and control sensor manufacturers aren’t all over this opportunity. They should be driving this big, exciting opportunity. For now, we have to settle for Cisco and GE arguing about whether to call it “Internet of Things,” “Internet of Everything,” or “Industrial Internet of Things.”

You can download the presentation here: TSB_process_control_1601b.